RUVDS together with Habr.com continue the series of interviews with interesting people in the IT environment. Last time we met with Boris Yangel, developer of Alice voice assistant made by Yandex.

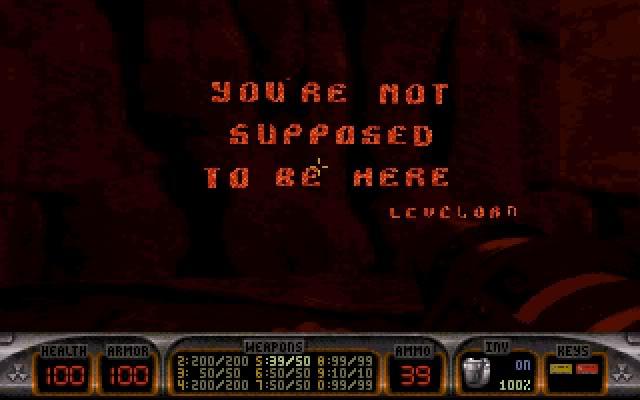

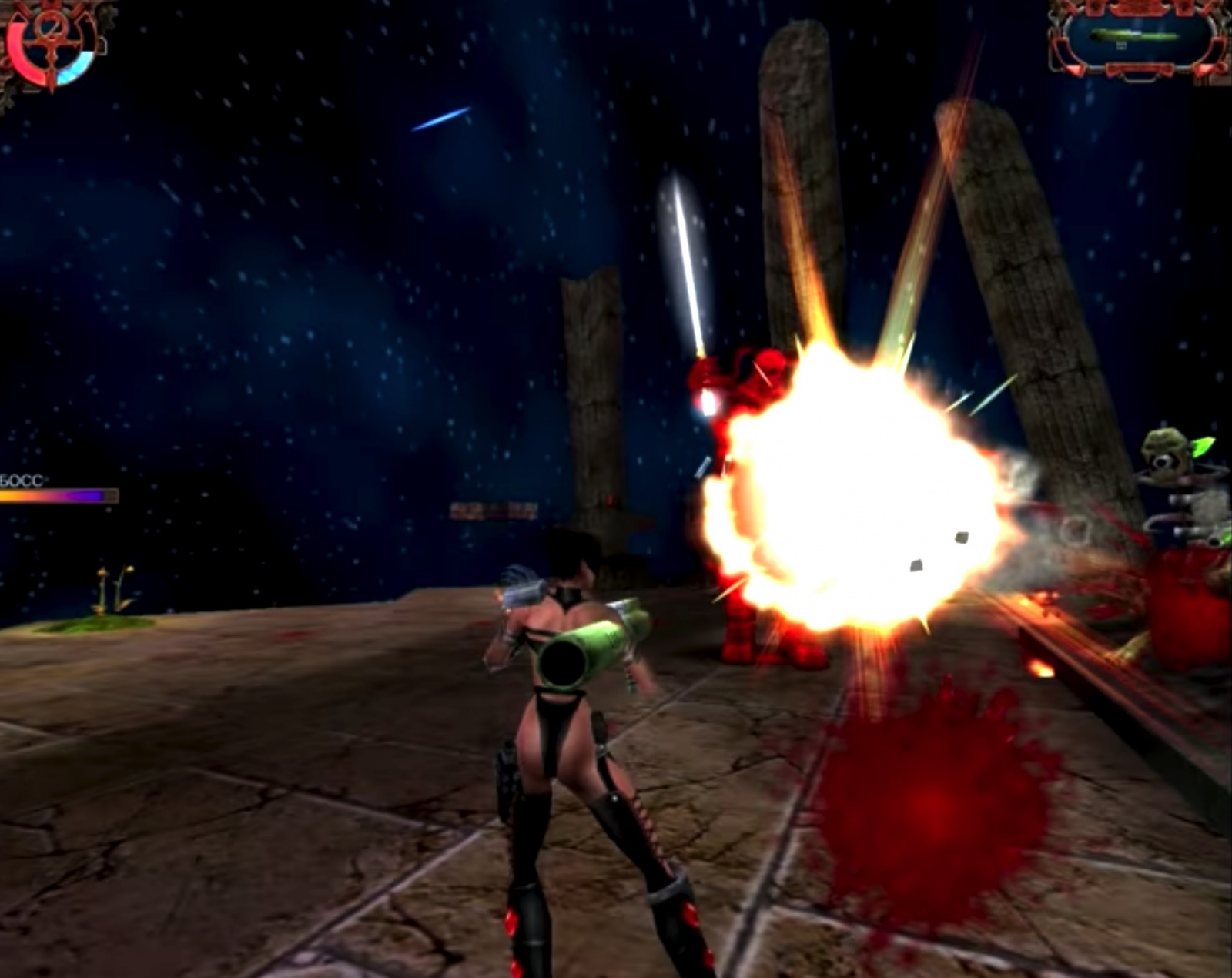

Today we bring you an interview with Richard (Levelord) Gray — level designer of such legendary games as Duke Nukem, American McGee Alice, Heavy Metal F.A.K.K.2, SiN, Serious Sam. And the author of famous phrase «You are not supposed to be here».

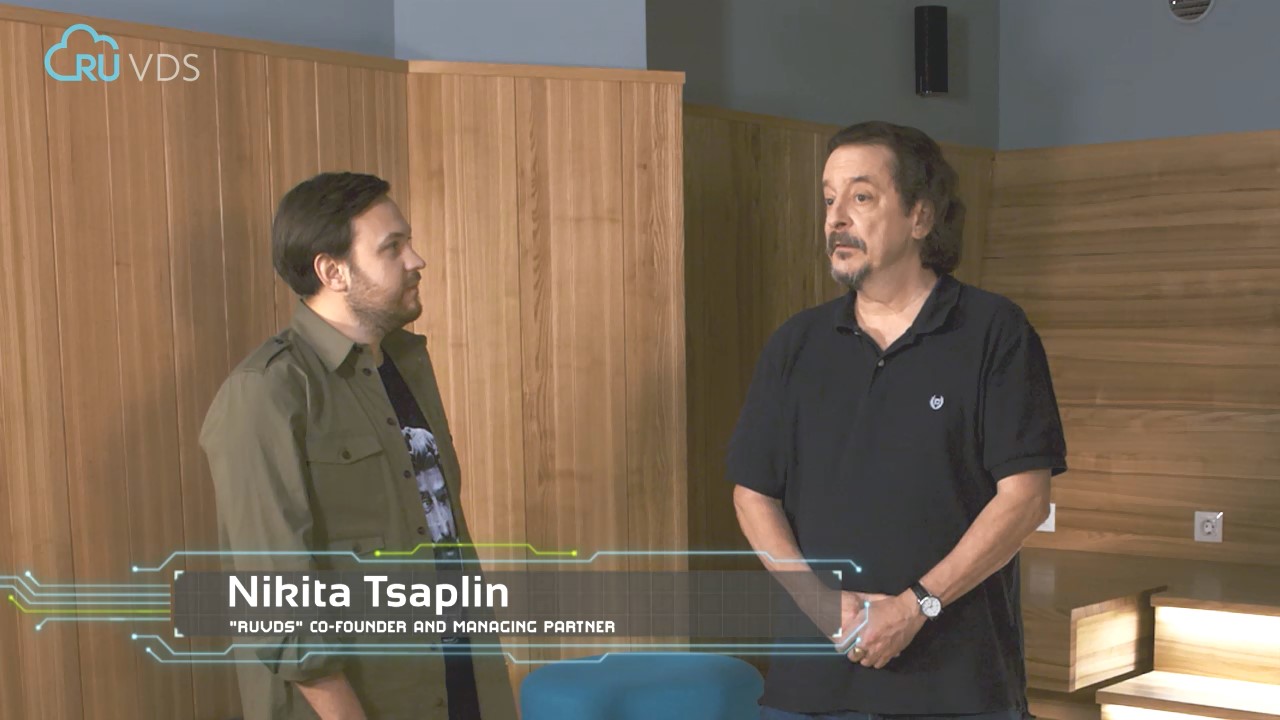

These who speak to Richard are Nick Zemlyanskiy, editor of Habr.com, and Nikita Tsaplin, co-founder and managing partner of RUVDS company.

→ Text and video in Russian

Editor of Habr.com Nick Zemlyanskiy:

— Hello, my name is Nick Zemlyanskiy, I am editor of Habr.com, and today we’re gonna talk to Richard Gray, great, famous level designer, founder of Ritual Entertainment. Hello Richard!

Richard (Levelord) Gray:

Hello.

Richard, we know the great things you’ve done in game development, from levels of Duke Nukem with its famous «You're not supposed to be here» easter eggs to design of American McGee’s Alice levels, these tricky levels to «islands in space» deathmatch design, to Heavy Metal F.A.K.K2 and SiN. And I know you even helped Croteam with Serious Sam, which is very popular game in Russia. So after all, what do you think stands out of this list for you? Or maybe I didn’t name something… What do you think is the biggest?

Well first I must correct, I only helped a little bit with Alice, that was Rogue Entertainment’s game, and towards the very end we helped. Ritual, we only helped, some of us. I helped them during the last crunch mode. But that was all their game, I just entered when they need a help. And Croteam… I never did anything for. They just… I thought Serious Sam was one of the coolest games to come up because there was nothing but shooting and killing things. It didn’t have all the gizmos, all the stuff that started happening with games. It was just a lot of guns, a lot of ammo, a lot of monsters. So I told them that and they put my endorsement. I said «Croteam has game». So that’s the only thing I did for them, the game was all theirs.

Can you name one thing that stands out of all the others that you’ve done?

It would have to be Duke Nukem, the very first game I worked on. Still after all these years it’s the one. People don’t remember me, people don’t remember my name, but all I have to do is to say «you’re not supposed to be here», and they say «oh, you’re that guy!». Duke Nukem was the biggest and best for me. And the most fun.

Yeah, that was great. So after this introduction let’s get to the very beginning, maybe even the time when I haven’t been born yet. How did you come to games, to game industry?

For me it started back in the early 1980s. I was making business application programs for company. And back then the machines we were using had the old-fashioned cards, the computer cards. You would write one line of code on, put the card down, one line of code, put the card down. Punch cards. And maybe one dumb monitor to watch what’s going on. But the company I was at got a brand new Hewlett Packard mainframe computer. It was a very big step up. Jump disks and monitors for everybody including the programmer who was my boss and I. Somewhere one day they bought a new mainframe Hewlett Packard and I found a little subdirectory called Games and there I found a game called… it’s known as Adventure but it’s called Colossal Cave.

It was a simple text adventure. The game would tell you you’re in a room and to the left there’s a door and to the right there’s a door. And you would say go right, go left. That was it. You would find treasures and you would lost. But right then I was hooked on games, I thought I had to do this for living. And at that time the only games were arcades, arcade games. Nintendo was out but there were simple little games with pixels for graphics. But I made in COBOL, which is a business programming language, my own text adventure game. I used ASCII art to do poker games.

But I knew I couldn’t make computer games, write engines, because you have to be very smart to do that. So I went to university to take computer engineering, thinking that would help. And I did that. Six years later I graduated I still couldn’t make, I wasn’t just smart enough. So then I went to an aerospace company to do software engineering there. Two years later a game came out. First Wolfenstein came out, and that was a sensational game, the very first real shooter, first-person shooter. Then DOOM came out shortly after that, a year later — again a fantastic game everybody knows. And then for me the critical point was when a free utility came out called DEU, DOOM Editing Utility. Which allowed everybody — and Id said it’s ok to do — you can go in and make your own levels.

The very first thing I do was: I went into one of the DOOM levels called E1A1, the very first one. I went in. In the very first room you come to window you could look out. But you can’t get through, it’s too low. I went into the editor, lowered the floor, raised the ceiling, went back into the game. I could walked through! It was just like seeing God for the first time. I couldn’t believe. And this is how I realized I can’t program, but I can make… It was called level design by the people who did it — John Romero etc. But the outside world didn’t know who the level designer was yet. But I thought this is what I have to do, and that’s how I get started. I spent every moment — it was a true passion for me — I spent every moment I had outside of work, weeks and nights just making levels.

So let’s find out some details of that period. You sent a diskette with your levels to Id Software. What did you expect from id? What was the answer? Did you wait too long? How long did you wait?

I’m still looking back and laugh. Laugh and I also feel good about myself. Again, I wanted to get into games for so long, by now this has been 10 years of me thinking I wanted to do games but the thought «naaah, I can’t do it». And then here comes level designing. I just had this passion. Even if I didn’t get hired I would still be making levels and doing game stuff, even know I wasn’t getting paid for. But I thought I gotta try. I took that four levels to Id. They were received very well on CompuServe, I got good comments. I put them on a floppy disk, wrote a letter (I typed on piece of paper), put them in an envelope and mailed. You know there was e-mail but there was no sending data back and forth. Like in the old days I mailed it to Jay Wilbur who was the CEO of Id.

I thought they’re not gonna open the envelope, I’m sure they get thousands and thousands of fan e-mails. But I did it anyway and I sent to them. I think it was about a week later, maybe two weeks later. I was going to work as usual and I came home. It was the old-fashioned phone with voicemail, it had a tape recorder and the light was beeping. I picked it up, it didn’t have ID, I had to listen. It said «Hello Richard Gray, this is Jay Wilbur». And I almost pooped in my pants, I just… «holy cow, I can’t believe!». A it was really nice, he said «sorry, this is great idea». I’ve sent a letter saying «this is such a great game, and it’s a great engine, and if we could just… if you let me in my team, make new art, we can make WWII version of DOOM or make a...». We know now it’s just a reskinning, but it was something that wasn’t done much at all. He said «sorry, we can’t let you do that, but thanks anyway». But that made me even more passionate.

By that time I was working on Blood levels, I already had my foot inside the door.

Co-founder and managing partner of the RUVDS Nikita Tsaplin:

Tell us a little bit more about that time. Can you describe your typical workday back then?

Well, it’s pretty much the same, it’s called «crunching» in the industry, when you work almost every hour of the day. And you work on weekends. We were in that, that’s how we worked. I’m almost all over games, when I look back. It wasn’t so bad for people like me who weren’t married, but for people with family… A typical day would be: gamers start late in a day usually, 9-10 o’clock.

Like software developers?

Like software developers, yes, they’re part of that group. And they would stay until 10 o’clock sometimes, midnight. Sometimes sleep in the office or race home, wake up a few hours later, have a shower, come back in the office and just keep doing that for… a typical game would last 1,5 years. It’s worse and worse as you get closer to the end. You do sleep in the office, sometimes for weeks. It’s just easy to lay down on the floor near your desk than to drive home and drive back. It could be brutal but that was typical. But it was still fun making games though…

In some series today we can see that software developers of that time look like small project teams. How did game development teams look at that time — the same or there was some difference?

Pretty much the same as far as I know. I never worked in software development. I was software engineer and programmer but never worked in software company. But we had very small teams — in Duke Nukem there were probably 8 core members and another 4-8 people who come and go like contract artists, like that. Very small teams, all Duke Nukem levels were made by just two people. And nowadays 20 people can work on just one level. So yeah, I miss those days too.

So actually you created easter eggs…

No, you know, I’m not the first one to do easter eggs, by far there were easter eggs in games since early 1970s. And then the one who’s famous for doing easter eggs, hidden stuff, is John Romero. In DOOM hidden stuff is all over. And not just John, many designers do. But for some reason “You’re not supposed to be here”… I just made this and I don’t know why… Actually, two people, we were talking before people could recognize me with moustache and long hair. One said “this is Levelord” and the other said “who?”. “Richard Gray, Levelord” — “Who?” — “You’re not supposed to be here.” — “Oh, that guy!”. So I don’t know why that was. And Allen had just as many, he had easter eggs hidden all over the place too. But that was for some reason and I can’t tell why.

Another year were movies a lot of times when actors were doing their parts, and one of them was “look at the camera and wink”. Acknowledging they’re on film. Maybe it’s because of that, it was me, level designer: “I know you’re here in the game, you’re not in reality”.

That was something like… you know in theater there is a term which is called “the fourth wall”. So with this phrase you’ve broken the fourth wall.

Yeah, you broke and you’re behind the seat now, yes.

Editor of Habr.com Nick Zemlyanskiy:

Let’s get back to the old times. How did you come to your principles of level design?

I am not sure… I mean there’s obviously a formula. For making a level you would start with an idea, you would draw diagrams, write things down so you can remember it yourself and explain it to your other colleagues, what you’re going to do. Then you make a very simple version of the level — no lighting, very little texturing — and get the gameplay to work, the critical path of the player, where good things are, where bad things are. And then do the texturing, the lighting, and do it in stages. You mean coming up with ideas when you say making a level? I’m not sure what you meant: actually making a level or thinking of the idea of what to make.

I meant what is important in making levels?

Oh, oh, oh, it sounds like a stupid answer, an obvious answer: of course, it’s gotta be fun. That really is the only consideration: is it fun? There are so many different ways a level or a game can be fun that you can’t just say «this is...». It’s gotta be fun on the top and of course right below that it’s gotta perform ok. Again, most games being on the knife edge of new technology, and everybody’s machine at home is going to be older. You’ve got to worry about framerate. If a game is gonna go real slowly, it doesn’t matter how fun it is. That’s gonna ruin the fun.

But after that, rather than a technology, good examples for me, the two best examples would be Tetris, which is a very old game. You couldn’t have a more simple game, but it’s still very popular — as far as I know, for me, I still play it. And the Angry Birds! You couldn’t have as more as simple game, as far as what makes a game fun. It’s just basic physics engine, you know, throwing things and using physics to help them fall. Great level design! I’m not saying it’s a stupid simple game like that, I mean it’s just absolutely perfect and it’s the most simple set of rules of how to make it fun. There is even — I still can’t believe this — there’s even Angry Birds underwear, Angry Birds cereal, Angry Birds soda, everything. It’s a great game.

So it just has to be fun. There are so many different ways depending on type of the game. You know where you’re in a shooter, if you’re gonna make a shooter like I used to make, it’s pretty much like an action movie. The game is made of usually three missions, you know, episode 1, episode 2, episode 3. You want the whole game like a story. You want it start out slow, build up action and intention, then come up to climax and drop off either a win or loss but either by satisfactory. If you lose you go back and do it again. If you win you’re like «oh my God, I survived that». The whole game is divided into three, and each of those episodes has the same crescendo, going up to climax. And each level has the same thing.

Sometimes you break the rules and just drop off the person in the middle of big battle but typically there’s the formula of making a great level.

There are so many things. The balance — as the persons going through, you make sure they have just enough ammunition and health, and there’s also enough interaction with bad guys. You don’t wanna make game too easy, you don’t wanna make it too hard. I met a lot of times games — I know I was guilty of this — I would take it something clever or tricky. I think I’m so smart, I’m gonna trick and fool the player. No, that’s not fun for the player to be tricked and fooled. It has to be good-balanced gameplay.

I’m sure a level is like a restaurant, where you’re gonna go, have a meal. The food has to taste good — it’s gotta be fun. But restaurants have ambience, and it also means. You know the restaurant looks good — if it’s a sushi restaurant, it looks like a sushi restaurant. The food itself, when it’s served, visually it looks good before you even taste it. The same with a level: it has to look good, you have to feel like you’re in. If I make a level in Los Angeles you have to feel like you’re in Los Angeles. Or apocalyptic or… all the things have to come together.

Tell me about the atmosphere. I know you were making Duke Nukem in 3D Realms and just nearby Id was making Quake. They were going to be big competitors on the market. How did you communicate? Did you communicate at all? Were there any secrets about things that are widespread now?

It was always known for, I guess, because they knew they were the best. I guess because they knew they’re best. I don’t think they ever felt there was competition for them. They were always very open and helping. I was always well-impressed. One day we even… towards a few months away from finishing Duke Nukem and feeling good about it. I knew we worked like dogs, I don’t know if it took crunch, I was 10 years away from game industry. But you’re working every hour to make deadlines, to finish the game, the quicker the better. So there’s no time for socializing so much. One day we go over and visit Id. I remember, again, I knew Duke Nukem was gonna be a good game at this point. We went over and John Romero showed us — «come on, you gotta see this, you gotta see this». It was him in one of his Quake levels. He turned godmode on, he was standing facing this way. And I think there was a shambler — a real big monster in Quake. It was coming from the back as real 3D model not sprites. And the shadow came out!

First I was «oh this is so cool». Then I thought «oh shit, there goes Duke Nukem». You know I saw a real 3D game, models and shadows, the lighting and everything. In Duke Nukem actually Allen Blum and I had no light. If I wanna this floor to look like it was lit, I have to make the texture look like. There was no light in Duke Nukem, level designers had to do all that kind of stuff. In Quake you just put the light source and it will do.

Today I look back and think «wow!». The transition from sprites to real 3D models. John Romero is still a hero. I was sitting with him looking at one of his levels for the first time, in the back of my head there was «I’m sitting here in Id office with John Romero showing me one of his levels...». And the other voice said «You just lost your Duke Nukem, Richard».

You had many great ideas but technology could let you down.

That would happen many times when you want to do something but just can’t do it. For instance in Duke Nukem you could only have one floor in any place, you couldn’t have floor above a floor. But Allen found a way to trick the engine. If you remember the very first level, Hollywood Holocaust. It’s got a spiral staircase that in fact goes up to where the other film projector room is. And you look down — I mean he figured out a way that you could fool it by putting a floor above a floor as long as you couldn’t see both floors at the same time. And so that worked. The limitation of technology made Duke Nukem stand out. People knew: «Wait a minute, there’s floor above floor, it’s not supposed to do that».

We did other tricks with the same type of thing. I had one room in the middle, and in the each corner there was a drophole. You’re jumping through the holes down, and there another room of exact same size but different theme. And there was a hallway around that middle room. You could go around and in the hallway you could see one room, go there, see another room, in the same place. A different room but in the same place. There were 4 of those. You go in the room and drop down to each of four. It was just crazy kind of because the engine...could do a lot of things, but you couldn’t do stuff like that.

You mentioned that work of level designer now and then is a cooperation between him and many other people. Can you tell us about the greatest people in industry you’ve met?

I got it early in game industry. I met so many people… many companies, many people. Many of them are just fantastic. But back earlier… I found a text adventure game that got me interested in games. Then I went to university, and in university I bought a Commodore 64. I bought a few games, I wanted to play games so I would know games. Then I bought Ultima IV, Richard Garriott’s Ultima IV and started playing.

I had a pretty good GPA, my Great Point Average in school was pretty good. Not perfect, but I was doing well. Ultima IV came out and my GPA — I still had year and a half to finish school — my GPA started going [down], because I just couldn’t stop playing: one more level, one more level… By the time I did graduate my GPA was that close to not graduating because of that one game.

Speaking of famous people. I met Richard Garriott a few times and he’s still now [raises hands]. Often you have heroes and you have a chance to meet them as normal people but Richard Garriott is still woaaah…

Co-founder and managing partner of the RUVDS Nikita Tsaplin:

By the time you found Ritual Entertainment you have already had great experience in industry. What were the key principles that guide you when you founded your own studio with your partners?

I don’t know, I only made Duke Nukem. By the time we left 3D Realms, Duke Nukem had just been released. Although we had an idea that it was a great game, we didn’t know, we just wanted to go out and around. For me it’s called «primadonna syndrome». I thought I was wonderful, I thought I was the best and I wasn’t being treated good enough by 3D Realms. So I go out and make my own company with other guys. A lot of us was there. Of course it’s even worse when you’re the boss, when it’s your company, you’re not free to do whatever you want. But there was nothing really that I brought with me from past experience — other than having a great time making Duke Nukem and then trying to do that again.

Our very first job in Ritual was the first add-on pack for Quake. That did very well, it was very well-received. It was the same type of feeling when we all knew what we’re doing, and we all did it well, and we had fun doing it. But nothing is more from Duke Nukem than knowing how to make a game

How did you combine management and level design duties in your job? Because before you found your own studio you worked only on level design. And when you start you own business you should be into management too.

We should make it clear. You keep saying it was just me, but there were 6 of us — owners of Ritual. One time there were all owners. There were nobody else, everybody was an owner. I was just a level designer, I didn’t found the company. The 4 original owners, they left 3D Realms first. They founded, they created the company, and then I came in later. So I had no, I enjoy having no responsibility with managing. We had a CEO who took care of business.

So you divided duties between owners? You did the level design and the management was duty of other members?

Yes, it was others’. I don’t like being a manager and we had others that were much better at it. I’m not good at management, I’m good at making levels, and that was all i did. Looking back I think we all agree it’s very bad idea having 6 owners. It’s like one boat with 6 captains. Or having 6 Popes.

So if you start game design studio again, you’ll be the main and the only one owner?

Oh, again, I’m a very bad manager, very bad boss. I’m not good with people. I don’t think I’ll ever start a company again. I’ll do like I’ve already done. I’m the boss, I’m the employee, I’m the company, because there’s just me. There were the best 3 years, the time I was doing indie games. No meetings, no documentation, no commuting, no schedules — just making levels and art. I did everything I can program and art. I would never start another company. Unless someone who’s listening says «Richard, here’s 5 million dollars, just do what you want to start a company». Then I would do that. But that’s not gonna happen.

I’ve heard from one of your interviews that you retired from Ritual Entertainment due to changes in industry organization. What problems did you face to make such a decision?

For me it got too complicated, both programming games and playing games. I stopped playing games too because it became… I like first-person shooters. For me that’s a game that has ammunition, health and bad guys trying to take those away from me. That’s it. That’s why I like Serious Sam so much when it came out. There was nothing… maybe 5 keys on keyboard and a mouse, that’s it. None of these gadgets, gizmos and «you need to do this and find that».

Then developing games. Instead of one level designer being on a level, there’s 5, 10, even more people on that one level: artists, people doing the lighting, people doing the… and that’s necessary not because somebody wants it that way. But that just stopped being fun for me. At that time I was single. I don’t spend money, I have a 20-year-old card, I paid the house off early. I looked in my budget and I thought «I have enough money for 20 more years of living». I’m also older, I was 20 years older than most of the game developers. I was 50 years old and I thought «naaah, I’m tired, I’ll just go home, make my own games at home and just do whatever I wanna do». That’s what I did

I heard that you helped some universities to start level design programs. How did it look like? Do students take some examinations? Did you hold examinations?

This would be in Dallas of course. A few of us — Jennell Jaquays, John Romero, Tom Hall and quite a few others — we were volunteered to go help program get started. They asked me what was good for level designer, asked Jennell for art, so we helped them start up. There was funny watching the head of the school trying to tell the higher administration: «No, no, this is cool, we can get some money from it». And now of course everybody’s jumping on. It was like a fire, a match and a gasoline, it just «poofed» once it started.

Which subjects are included into level design education program?

Level design, that’s it. All the things you need to make levels. The most important thing that you can’t learn by being at home and self-teaching yourself at art, level design or programming is how to make something with more than just you, the teamwork. And that’s a big thing at schools, I know. Because at home alone I know how to make good levels but I don’t know how to sit next to four level designers and make a level. It’s not my level, it’s the game’s level. So that one thing they provided is pretty helpful.

And what’s the criteria to understand that a student is ready to make cool levels or should work more?

It’s not like university physics or maths when they give you tests and say «Do this problems and give us the answer». You make a level. And it’s not you making a level, it’s you being a team in class. This class is for the artists, this class is for the level designers, programmers, game designers. They’re doing their thing, they put together in groups and each group makes a game. That’s how they’re based as far as I know. I’m sure there’s some tests, but…

You don’t go to school to learn how to be chef. You don’t take tests, you cook food and show them: «that is, I made this». So it’s very similar to that.

Editor of Habr.com Nick Zemlyanskiy:

You know many retired professionals finish their career with teaching others what to do. But I know that in recent years you made new levels for new Duke Nukem 3D 20th Anniversary World Tour. Can you please describe all the process of making level on this example?

That was one of the funniest things. Don’t tell Gearbox, but I would have done that for free.That was just incredible. 20 years have gone by, and Randy Pitchford managed to get myself and Allen Blum, the two level designers. We got Lee Jackson who did the music, and… I apologize I can’t remember everyone right now. We got a lot of original people and we used the same Build engine. It was enhanced, it now had 3D, it could change Build engine format to actual 3D, if you wanted to play with real lighting, dynamic lighting and everything. Or you could play with the old version if you wanted to be nostalgic.

But for me to go back in… I guess Allen and I spent a year part-time, not full-time. Just like in the old days he did half the levels, I did half the levels for a new episode. And we decided to do a world tour. Duke goes to famous cities to save the world. The first city I picked was Moscow. He picked… all of his cities were american except for Egypt — Los Angeles, San Francisco. I went to Europe.

It was very strange to… we spent a year and a half making the original Duke Nukem, crunching, every waking hour we were in the office, weekends, everything. So a big section of my brain has been burned in making Duke Nukem. It was fun but very, very brutal, hardworking. Then forget about it for 20 years. And then comeback.

I was in the Build. Allen was always smarter than me. What I mean is I was usually asking him questions: how do you do. Allen would be sitting there [on the right] in the original Duke, I’d be sitting here. And I [was turning] with «Allen, how do you..?». Now I caught myself. I’m here in Moscow now, 20 years later in my apartment. I wouldn’t physically look but I get this urge of asking «Allen…». There was no way, Allen was in California making his Duke levels and I’m in Moscow but still there’s so much in my head, the old days.

It was a lot of fun. The things you can do now… you had to be very sparse, you couldn’t do very many things with geometry, sprites and stuff. Now you can just do whatever you wanted because the machines now can handle it like "[yawns] Davay...". I had a lot of fun making it. Here Duke Nukem talking at the background.

I never heard about sales exactly. It’s on steam of course, Xbox and Playstation. I expected a huge fanfare of e-mails and stuff but not much. Who knows… I think because the technology is too old, it is an old game and the gamers know of Duke Nukem, but they don’t know [the game itself]. Like old movies. I like old movies from before I was born, black-and-white. But a lot of people won’t watch, just because they’re black-and-white. But that was a lot of fun doing that 20th Anniversary.

After Duke Nukem are you doing something in game development? Maybe you help people with level design?

I have done some helping with level design. When I very first retired, I got home in Dallas and made two hidden object games, all by myself. It was the most wonderful, for all the reasons that I left the industry. It was the most wonderful place to go: no meetings, no commuting, no documentation, no scheduling, no deadlines. I can just make games without any concern other than just a game. And I spent 3 years, made two hidden objects game. They weren’t great of course, but for one person I still look back and I think «Molodets, Richard, good job». They made sufficient money — in fact I was surprised.

Since then… my mom got sick. She’s better now but my mom got sick for a year. I went to help her rehabilitation and then came back to Dallas. I stopped doing everything after being a year away with my mom being in such a bad shape. Then all of a sudden I found myself in Moscow, married, with a daughter.

Now I’m retired. I don’t do much anything professionally, but I do play with Unity and Unreal. I make little prototypes and try things, just for fun. Now for the very first time I’m making a new game for Android, on handheld, which I thought I would never do because I don’t like playing, it’s small, I’m old, I can’t hit the buttons quickly enough. But now with this game I’m thinking: «Oh no, wait a minute, this is kinda cool». And you know, you’re going on subway, everywhere you go people playing on handhelds, it’s the place to be.

I don’t so much helped people. I have helped a very good game company owned by my friend, called Game Garden. I’ve helped them a few times with one of their time management games. I have another friend I helped with a bubble shooter, But nothing serious like making my own game and releasing it. Though I might soon…

Co-founder and managing partner of the RUVDS Nikita Tsaplin:

— What is your favorite of «Made in Russia»? Maybe some food, places, weather…

That is a very difficult question I’m asked both here and in America. «Why? What’s over there» And I can never pick because… the only thing I don’t like is the winter, but everything else. As you can imagine, leaving your home, everything behind. I still go back twice a year but everything I know — family, friends, everything — is back there, so everyday one point or another I miss something that’s not here. Not that we don’t have it here but it’s not what I’m used to.

But there must be reason why I’m here. It’s because I like everything here. Russian people are fantastic, one of the best people I know. Generally, we have bad people here, but just… I like… The food. I’ve put on 10 kilograms since I’ve been here. I love Moscow. My favourite city before I came here was New York, and Moscow has the same feel. It’s fast, it’s not dirty bad, but it’s old city, it’s busy with all cars and everything. And I can’t pick one thing that I like here. I like the whole thing. I like Russia very much. And I wish more people would travel both ways. Because I have Russians saying: «You’re a nice American». Yeah, Americans are nice people. And everybody I know who’s come from there over here, they leave saying: «Why is this trouble with Russia, it’s just fantastic!». For all the same reasons I have — the people, the food, the cities are fantastic. It’s a shame that we can’t do more travelling back and forth.

It’s not propaganda. It’s not we’re hearing bad things about Russians over here, bad things [about Americans over there], we hear nothing. And so we have to make up, because the politicians — the sort of people I don’t like — the politicians get this shit going on. But anyhow: if you have a chance to come to Russia, do it.

It was so difficult to be homesick last summer because of the World Football Championship. Did you visit some matches.

We didn’t go to matches but we did go downtown. And that was one of the funniest… I thought we did great job supporting FIFA matches. But is was funny for me. I came from Texas, and there’s a lot of mexican influence. I always loved Mexico — the people, the food, the same reasons. I was over here feeling homesick overnight, we walked on the streets. There’d be groups of nationalities, we came up and I started hear mexican music. And here are Mexicans doing their thing. I felt like I should come over and say «hi» like we’re friends. Because we’re over here, there are Mexicans and I must know one of them. It was nice here lately, the Spanish and everything. I thought it was great, we did a great job, the city looked so cool. But I’m glad it’s done.

Can we ask you to say something from Duke Nukem, your favourite phrase, just for camera?

You know I can’t even think… Come get some!

Editor of Habr.com Nick Zemlyanskiy:

So many young people today want to make games like John Romero but don’t know where to start: to start their own project or go to game studio to find their place. Can you give some advice here?

The first thing: I have been asked this question since Duke Nukem first came out. People come and say «I wanna make games, how can I get in...». I always have the same question to answer their question: «If you wanna be a level designer, what levels have you made?». And I see them «Oh, I’m not making any levels yet but I really wanna be a level designer!». I always tell them: just like me before, I wanted to get hired, but before I even asked anybody I made levels. And I would have not stop making levels even if I didn’t get hired. Again, it’s a passion. So many people ask this question and they really don’t [want to]. Even today they ask «How did you get in?» I ask «Artist? Do you have a portfolio art that you’ve done?» «Programmers? Have you got any mods?» For me somebody’s saying «I want to make games» is like… I like pizza and I wanna work in a pizzeria. Because eating pizza and making pizza are two completely different things. Not the same. If somebody wants to make games — levels, art, program — they should be doing that already. There are free tools out there, there’s no excuse of not doing it.

If that fails, you should go to one of the schools. We have great schools here in Moscow. The Business School of Management and Information. Around the world back in America I helped get started two universities. There are private schools. So nobody should ask that question, the just should be doing. It’s very obvious. You did it already and you have something to show to company that would hire you. Or you go to school and go through that. But you come up and think I’ve got a magic answer: just google this website, click Yes and you’ll be in. It’s not like that of course. Again, most people who say «I wanna be in game industry» have nothing to show. They just play games and say «I wanna do that for living». I wanna work in a pizzeria.

Or another one. This is for mature audience if you wanna use it. It’s a lot like… No, I won’t use that one. Pizza is good.

So this was Richard Gray, the famous Levelord. Thank you for your time Richard!

You’re very welcome.

Автор: ru_vds